The problem

There’s a common mantra in games design, in fact, it’s something shared in the design of most things - ‘Keep it simple'. This however directly conflicts with the urge most young designers feel to cram every good idea they have into a game.

As we become more experienced, we learn to pick and choose between our ideas. There is a shared understanding in the industry that often, less is more when it comes to mechanic design, however this often rears its head as some vaguely agreed upon notion that a design should not be overly crowded with features.

In addition to this, complexity can be the very thing that makes the core of a game interesting, and we often want to try to create systems that will give us depth through the possibilities of their combinatorial elements. So where do we draw the line?

The real key, is that it all comes down to pressure. Pressure is an interesting topic in game design, and it’s one that I’ll cover in more depth in the future, but for now I’ll simply summarise it for our purposes as - the time the player perceives they have to make a decision. In a turn based game, the pressure is low. In a third person action game, the pressure is higher - and if the enemy AI is advancing, threatening to flank you, then the pressure is higher still.

So we return of the question of ‘how much is too much?’, surely there is a better metric than merely relying on gut feeling, or blindly throwing builds at playtesters until they seem happy.

The rule

So with this in mind, consider the following rule: That when we ask something of the player, it should be the only thing they are being asked to actively think about and deal with. This is essentially about a person’s ability to calculate, to deal with problems in real time, to pay attention.

Now it’s important to note that this rule is a starting point. There may be times when you want this pressure to increase, or decrease to nothing, and I will explain why that’s important a little later, but first, to try and explain why this idea is important I want to present an example we will all be familiar with: Learning to drive.

When we got in a car for the first time, if we were asked to pay attention to everything - signalling, steering, observing, changing gears - we would be overwhelmed, we would probably neglect something and we would most likely crash. This might sound simple, but it’s a basic illustration of how the brain can deal with new information, and how people deal with new actions they are being asked to perform.

In this example, we also don’t actually need to remove any of the ‘mechanics’, instead we are introduced to them one by one in a safe environment until they become second nature. When they have become automatic, we can introduce more and more until we are able to essentially perform all at once.

So you can begin to see not only the importance of the rule of ‘actively thinking about one thing at a time’, but also one way in which we are able to include many more mechanics without overwhelming the player.

The key point here is that if the player is consistently being required to actively (and by actively I mean consciously pay attention to and calculate) more than one thing, then you know you have too many mechanics at that moment.

When and how the rule can be bent or broken

We can also see that conversely, as our players become more comfortable with gameplay, it can be important to increase the pressure of those mechanics, or add more to avoid the player becoming bored (enemies becoming more aggressive or adding more enemy types being the most basic example).

And of course in sections of the game where we actually want to increase the pressure to make the player feel stressed or overwhelmed, we can actually require them to deal with more things than they are used to at one time (think, having to unlock a door while you fend off enemies at the same time), perhaps more even than they are able to deal with (fighting a battle you eventually lose for story purposes). Be aware though that if you increase this too high, players may fall back on simple solutions, foregoing the interesting possibilities of your systems because they’re so stressed they don’t have time to think properly. Because of this, these moments should be the exception.

Techniques for adding in mechanics

This rule is restrictive by its very nature, so let’s look at some ways of circumventing these restrictions while not compromising player experience. Some of these are obvious, others less so.

- Learnt things becoming second nature allowing us to add more

This we’ve already discussed - mechanics that become second nature freeing up the player's mind to do something else. So, aiming then gives way to tactical positioning. Cover based combat gives way to enemy prioritisation and so on. This is done in almost every action game made to date.

- The simple practice of requiring different skills at different times

This too is done often in games. In boss design for example - we often have to use one skill and then the pattern of the enemy will change requiring us to use something different.

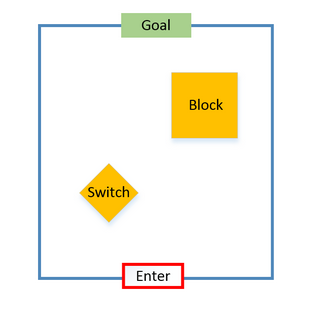

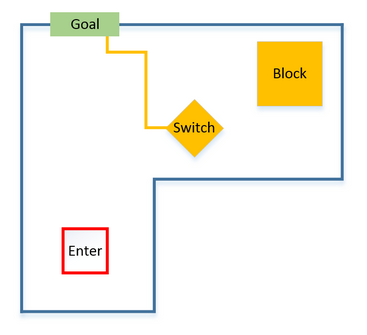

- Layers in level design

This is the simple idea that there are different places for different activities. A game that illustrates this very well is the recent Metal Gear Solid: V. They deal with the issue of complexity by placing different requirements at different distances from each objective.

At the very lowest pressure, there's nothing to consider, but you get breathing space to organise yourself. Further in, you can observe things and tag enemies, possibly use a long-range rifle. After that you get the different stages and ranges of combat. Of course you can do all of these things at once by charging in, but this is much more difficult and stressful. It also allows the player to set their own difficulty by choosing how slowly to approach.

An interesting solution to the problem of complexity: The pressures in MGSV

An interesting solution to the problem of complexity: The pressures in MGSV - Kishōtenketsu

The phrase comes from the inspiration behind the structure of Super Mario 3D world, and how that popularised this type of game structure, though it was by no means the first to do it.

The idea is very simple - instead of increasing the elements that a player uses as the game goes on, you simply change them. A mechanic is explored for a while and then thrown away, and a new one introduced (Though this is of course a simplification of these game designs)

Some examples of other games that use this format - Braid, Portal 2 to varying degrees, Brothers, Retsnom, Advanced Warfare (each level gives you a new toy you then never get again) and I’m sure many more.

Takeaways

So as you can see there are actually many ways to include different mechanics in a game without it becoming overburdened. We have a rule that allows us to maintain a default level of pressure in a game, and can show us when just one more mechanic is one too many, and when it may just need a new place.

This is the basis of how we sort, structure and cut mechanics in our games.

Jade from Beyond Good and Evil

Jade from Beyond Good and Evil Fetch and Delsin from Infamous: Second Son

Fetch and Delsin from Infamous: Second Son